ericnelsonavery@yahoo.com

Comments?

Mail to: ericnelsonavery@yahoo.com |

Themes |

|

Eric Avery -

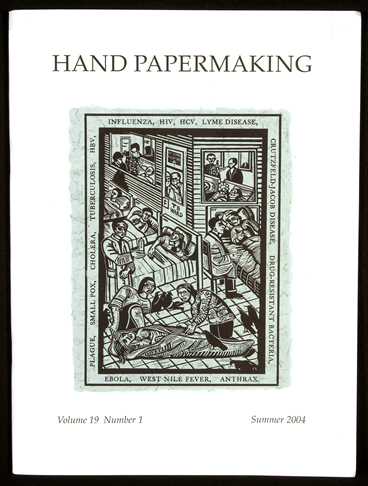

"Political Prints and Paper Making" Text by Eric Avery with illustrations Hand Papermaking, Summer 2004 |

| “The

artist who laughs has simply not yet heard the terrible news.” Bertoldt

Brecht (1)

I have always made prints. I became a physician. During the Vietnam War, with the encouragement of my printmaking professor at the University of Arizona, I applied and got into a medical school. He said that since I would always be making art and since art comes from life, I should make my life interesting. This was a terrible time in the United States. Besides antiwar protests, there were race riots and major cities were burning. A lot of men my age had to make hard decisions. I would have been drafted if I had not continued my education. Deciding to apply for medical school with a degree in fine art seemed radical at the time. In retrospect, it was not. We need more creative artists in health care helping to figure out how to make the world better. After I completed my medical training in 1978, specializing in psychiatry, I worked as a physician with Vietnamese refugees in Indonesia and then as medical director in a large refugee camp in Somalia. Cutting relief blocks and hand printing them helped me turn anger and sadness into indignant and beautiful works of art. From 1981 until 1991, instead of practicing medicine, I lived in a small Texas/Mexico border town and worked as a printmaker and papermaker and as a refugee activist within Amnesty International USA. This was another terrible time in the United States. Our government, under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Herbert Walker Bush, were supporting a terrible war in Central America and thousands of refugees were fleeing north for sanctuary. I made a lot of prints about this. In 1987, in a shop in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, I bought a small wooden basin with a washboard. It reminded me of the ribs of a starving Somalia child. I drew a starving child on the inside of the basin and then cut it as a woodcut. To print it, I had to figure out how to work with paper pulp. Papermaker and printmaker Susan Mackin-Dolan was working then at the Southwest Craft Center. She came to my studio in San Ygnacio and we figured out how to make molded paper woodcuts. |

|

|

Working with paper

pulp expanded my printmaking because it freed me from the flat print

surface. I could use any wooden object as a print template. My prints

became objects that moved off the flat wall and into low relief space.

Seeing Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s deeply gouged expressionistic

woodblocks in the Brucke Museum in Berlin gave me the idea of simultaneously

combining relief printing and intaglio printing of the cut marks. I

began to cut my relief blocks with the intention of printing both the

relief surface and the cut marks using paper pulp.

In 1992, as my friends began to die of AIDS, I returned

to medicine and combined both my medical and art practices in my

current positions at The University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB)

at Galveston where I am an Associate Professor of Psychiatry in the

School of Medicine and Associate Member in UTMB’s Institute

for Medical Humanities. Part of my time as a physician is reserved

for me to work in my studio. My art practice is to make paper and

prints and do art/medicine actions in public spaces. In my medical

practice, I am a psychiatrist who has specialized in working with

patients with HIV and Hepatitis C. |

|

Beginning in 1993, I took my medical practice into the protected aesthetic space of art galleries and museums in a series of art/medicine actions that educated viewers about HIV/AIDS. Paper was an important element in each of them. Toilet paper was printed with information on how to use the new female condom. Large Japanese Okawara paper was printed with linoleum prints of a peripheral blood smear and the life cycle of HIV. These were used as wallpaper for clinical art spaces. (Image 4, 5 and 6) Round molded paper woodcuts representing HIV were hung in several of these spaces. When these print spheres are filled with condoms, they become HIV Condom Filled Piñatas. (Image 7) |

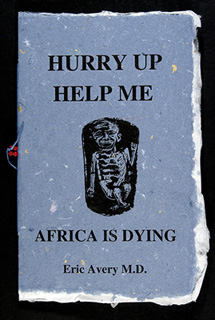

(Image 8) (Image 8)Cover Hurry Up Help Me Africa is Dying 2003 Single Section Book Letterpress on handmade paper Printed by Mark Attwood, The Artists’ Press, White River, South Africa Edition: 100

|

Besides getting

publicity and educating the public about HIV, these art/medicine actions

raised conceptual questions about medicine as a healing art and about

the function of art spaces. Jerry Cohn, Print Curator of the Fogg Museum

at Harvard University asked readers of her Print Fan Newsletter: “What

happens when medicine, usually confined to hermetic spaces such as

clinics and hospitals, is reintroduced as a healing art in the unexpected

context of beauty and human creativity? What happens when the protected

shield constructed by art museums against the existence of the transitory,

debilitating facts of human life is ruptured by medical practice?”(2)

In August 2003, I returned to Africa to attend the Impact Print Conference in Cape Town, South Africa. Five million South Africans - one in five adults - are living with HIV/AIDS. Six hundred people there are dying from AIDS each day. Bill Lagatutta (Tamarind’s Master Printer), Mark Attwood (a Tamarind graduate working in South Africa) and I proposed a two-part print action for the conference. It would focus attention on the egregious lack of access to life saving medications in South Africa and on the resulting orphan crisis. Hurry Up Help Me Africa is Dying (Image 8 and 9) was letterpress printed on paper I made from the clothes of HIV orphans at the Amazing Grace Children’s Home in Melelane, South Africa. (Image 10) New clothes were exchanged for the old ones. At the Conference, this single-section booklet, telling the devastating story of HIV in South Africa, was sewn together by HIV+ women from a craft collective outside Cape Town. Sales of this booklet raise money for the Amazing Grace Children’s Home. |

| If you believe

that information can lead to change, then bearing witness is the narrative

function of art and serves a social purpose. If one person, after seeing

one of my art actions, were motivated to change an HIV risk behavior

and did not get HIV, then this would be my evidence that art can save

lives. Art can also give hope. I use my prints in my clinic to do this

every week.

When there has been no cure in trauma situations I have

encountered at work, all I could do was listen to my patients’ stories.

Sue Coe says that witnessing without being able to change is the beginning

of empathy.(3) Empathic listening

is a form of therapy. When we tell our stories with our art, metaphorically

processing our experience,

then we have an opportunity to be healed, especially if someone is

listening. Indignant and trauma-filled prints and paper works are hard

to sell and art spaces generally do not like to exhibit them. The art

business is different from the healing business. Practicing medicine

in art spaces reminds us that art and healing were only sundered in

this past century and in our culture. Beyond the story, the physical parts of print and papermaking can be used to process and express a lot of emotion. Boiling fibers, cutting up rags and beating them, cutting a woodblock, printing with a press: through all of these actions the artist can psychologically sublimate aggressive and hurt emotions. I always encourage artists to consider becoming health professionals and to work in areas where you can become witnesses and helpers. When we get out of our heads and our studios and make our lives interesting, the artwork will follow. The art world may laugh but you will not, when you discover that your art can save lives. |

|

1. Mat Schwarzman, “Arts and Social Change” Course Description, San Francisco State University, Fall 1992 2. Marjorie Cohn, Print Fan Newsletter, Harvard University Art Museums, August 15, 1997 3. Sue Coe “Art and Activism” Course Description, Parsons School of Art and Design, Spring Semester 2003 |

|